Behind the Scenes of Go Trino Driver — Making Spooling Work for You

Introduction

This post aims to explain how we leveraged the Go Trino driver to make the most out of Trino’s spooling protocol. I’ll try to keep it short and sweet — first with a quick intro to the spooling protocol, then diving into how we orchestrated goroutines to squeeze out maximum performance, all while keeping in mind that we want to release resources from Trino as soon as possible (I’ll get into that).

Of course, we also had to balance that with controlling memory usage on the client side. I’ll share how you can tweak parameters to better harness parallelism — and really let your machine show off its power.

Direct vs Spooling Protocol

Direct Protocol

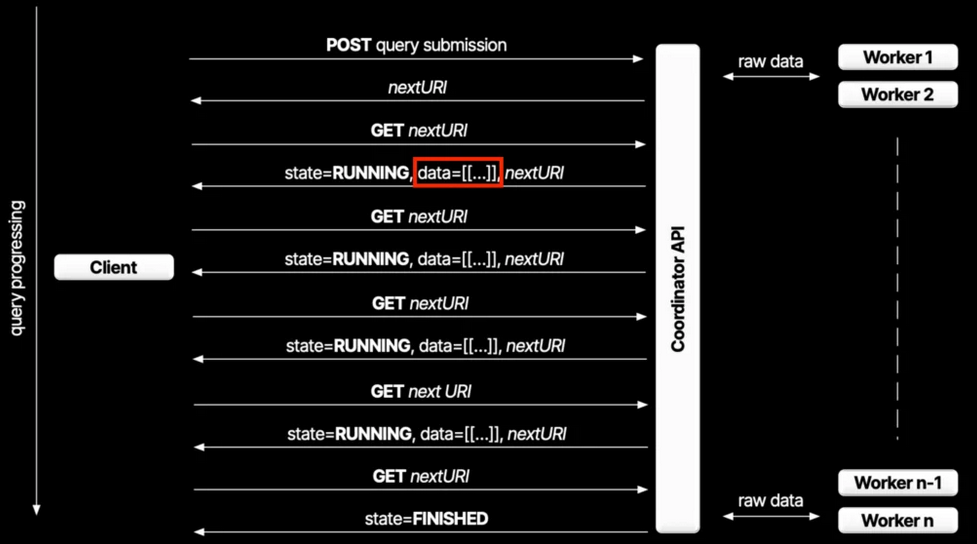

Think of the direct protocol like streaming your favorite show — you get data bit by bit. When the Go driver sends a request, it follows a chain of nextUris. Each response gives you a chunk of data (up to about 1MB) and a link to the next chunk.

Sounds simple, right? But here’s the catch: if you want to grab 1GB of data, you’ll be making around a thousand requests. And every single bit of data has to flow through the coordinator. The coordinator isn’t just passing data between workers and clients — it’s also busy encoding that data into the final format (JSON). That puts a lot of pressure on its CPU and I/O.

So, the direct protocol is great if you just want a small amount of data fast — low latency, no problem. But if you’re trying to move big piles of data, it’s not the best friend you want.

Spooling Protocol

The whole point of the spooling protocol is to get way higher throughput. Sure, it trades a bit of latency for that — but honestly, that’s a fair deal.

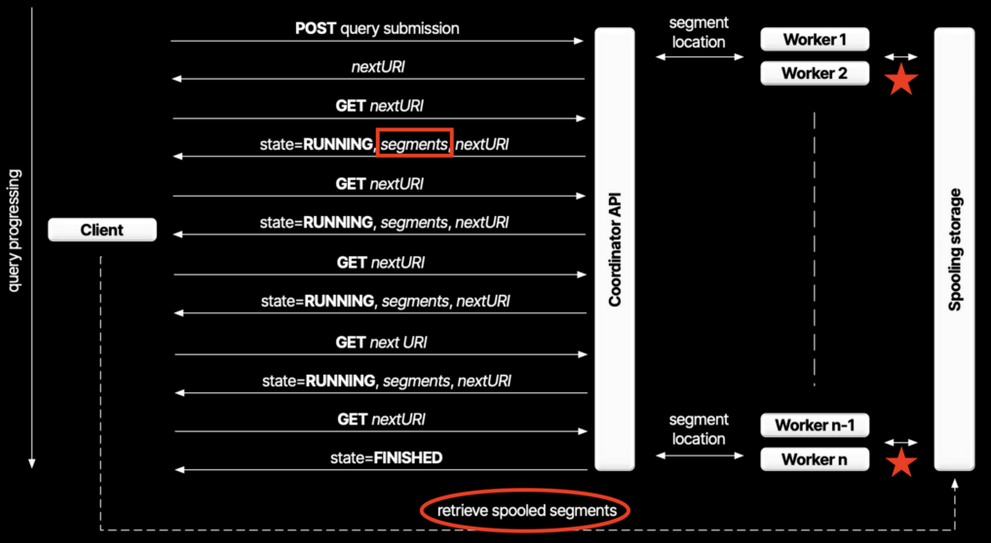

Remember how the direct protocol puts a ton of pressure on the coordinator? The spooling protocol tackles that by doing things differently. Instead of sending data straight to the client, it saves the data somewhere else — like S3 — and just sends the client metadata and URLs to fetch those spooled segments.

What’s the first thing that probably popped into your head? Fetching data in parallel from multiple sources with out go driver. Rock and roll! 🎸

One thing to keep in mind: if the result set is small or slow, it’ll still send data directly to the client — we call those inline segments.

Another key difference? You’re no longer stuck with 1MB per response. Instead, you get multiple spooled segments that can be much bigger (up to 128MB each!). How many segments you get depends a lot on how hard your workers are spooling the data. For small results, it sticks to inline segments — because hey, storage costs money. Once the data crosses a certain threshold, workers kick in and start spooling. That threshold is configurable, but we’ll leave the details to the docs.

So, what does the spooling protocol really mean for you?

- The CPU work of encoding data moves from the coordinator to the workers

- The heavy I/O of handing off data moves from the nodes to the spooling storage

- The client now gets more “data” — multiple segments to fetch

- Bigger chunks of data — 1MB max per response in direct vs up to 128MB per segment here

- Much better throughput, with only a small latency hit upfront

In short, spooling shifts the bottleneck away from the coordinator — pushing encoding and I/O to the workers and external storage — and gives clients the freedom to pull big chunks of data in parallel, boosting throughput without crushing the coordinator.

Go trino client

Alright — now for the fun part! 🎉

In this section, we’ll dive into how the Trino Go driver handles the spooling protocol, how it’s designed to maximize performance, and the key configurations you can tweak to avoid bottlenecks.

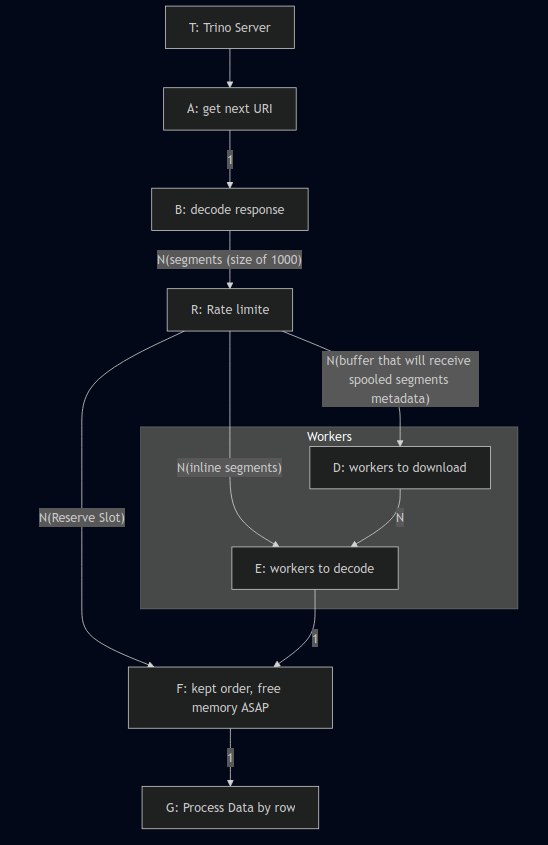

The diagram above shows how the goroutines are orchestrated inside the client — and that’s exactly what we’ll unpack here.

Think of this setup like a factory assembly line, where every worker has a specific job:

A - The Fetcher

This worker’s job is simple but critical: keep fetching data from the Trino server as fast as possible and pass it immediately to worker B. No delays, no blocking — just non-stop fetching. Why? Because the sooner we pull data from Trino, the sooner we free up the coordinator. That’s one of the key goals of the spooling protocol!

B - The Decoder

This worker takes the raw data from A, decodes it, and pushes it into a big buffer channel (with a default size of 1000).

Why such a big buffer? Because we never want A to get blocked waiting for B. If A blocks, we’re holding onto resources on the Trino server longer than we should, and we not want that we want to free the coordinator as soon as possible.

R - The Dispatcher (a.k.a. The Overworked Genius)

This is the smartest — and busiest — worker in the room.

R wears three hats (and only gets paid for one 😄):

-

It checks whether each segment is an inline segment or a spooled segment.

-

It routes the segment to the correct next channel based on its type.

-

It constantly talks to the last worker

Fto make sure we’re not overloading the pipeline.

This “rate limiting” logic will make more sense when we explain what F does, so hang tight!

D - The Downloaders (default: 5 workers)

These are your parallel download heroes. They take care of fetching the spooled segments from the storage system — and they do it in parallel. More workers mean faster downloads, but also more I/O and memory usage.

E - The Decoders/Decompressors (default: 5 workers)

Once a segment is downloaded, or is an inline segment it need to be decompressed(not always) and decoded. That’s where E steps in. Again, this happens in parallel with configurable concurrency.

F - The Finalizer (a.k.a. The Stressed-Out Worker)

This poor guy is always under pressure. 😅

F is responsible for delivering the data to the client — but only when it’s ready and in the correct order. F makes sure there’s always at least one chunk of data ready to deliver, and only then sends it out.

Also, F keeps R updated on whether there’s still room in the pipeline. This way, R knows if it should dispatch more segments or wait a bit.

By default, F can manage up to 10 segments out of order — but this is configurable to.

Why does this matter?

Imagine if R kept dispatching segments with no control — the downloaders (D) and decoders (E) could easily overwhelm memory. This flow control mechanism is what keeps everything running smoothly. But anyway is up to the users to decide what is best for their use cases.

Bottleneck

Now, let’s talk about the elephant in the room — the bottleneck.

The Go Trino client implements the standard database/sql interface. This is great for compatibility, but… it comes with a catch: it’s row-oriented and doesn’t support concurrency when processing rows.

So even after all our fancy workers have done their jobs — fetching, decoding, downloading, decompressing — we hit G, the final stage that processes data row by row. It’s like having a super-efficient assembly line ending with a sleepy old man packing boxes one at a time. 🧓📦

Even something as simple as writing results to a file in a CLI tool would face this limitation.

But hey — this Go driver is actually a solid starting point if you want to fork it and build a more parallelized solution. If you ever go down that road, I’d be more than happy to help! 😄

Conclusion

The Trino spooling protocol is a game-changer when it comes to fetching large datasets efficiently — shifting heavy work off the coordinator and giving clients the power to download data in parallel from external storage.

But great protocols need smart clients to make the most of them. That’s where our Go Trino client comes in, carefully orchestrating goroutines like a well-oiled assembly line. Every worker — from fetchers to decoders to downloaders — plays a key role in making sure we pull data fast, decode it efficiently, and deliver it in order without blowing up our memory.

Of course, no system is perfect. The final bottleneck — the synchronous, row-by-row processing enforced by Go’s database/sql — is a real thing. But it’s also a great opportunity for anyone willing to fork the client and push the boundaries further.

In the end, it’s all about understanding the flow, tweaking the parameters for your workload, and squeezing every drop of performance out of Trino and your Go client. And hey — if you feel like hacking on this, you know where to find me! 😉